Donald Trump’s plans for a second term are deeply influenced by Christian nationalists, people who believe that the Christian faith should be enforced by the government. Project 2025, a document developed by a consortium of conservative groups to guide Trump when he takes office, uses Christian nationalism to justify dismantling or overhauling key agencies of government to smooth the way toward an established state religion—and even advises invoking the Insurrection Act to suppress protest. According to the Public Religion Research Institute’s 2023 American Values Atlas, 55 percent of Trump supporters are Christian nationalists.

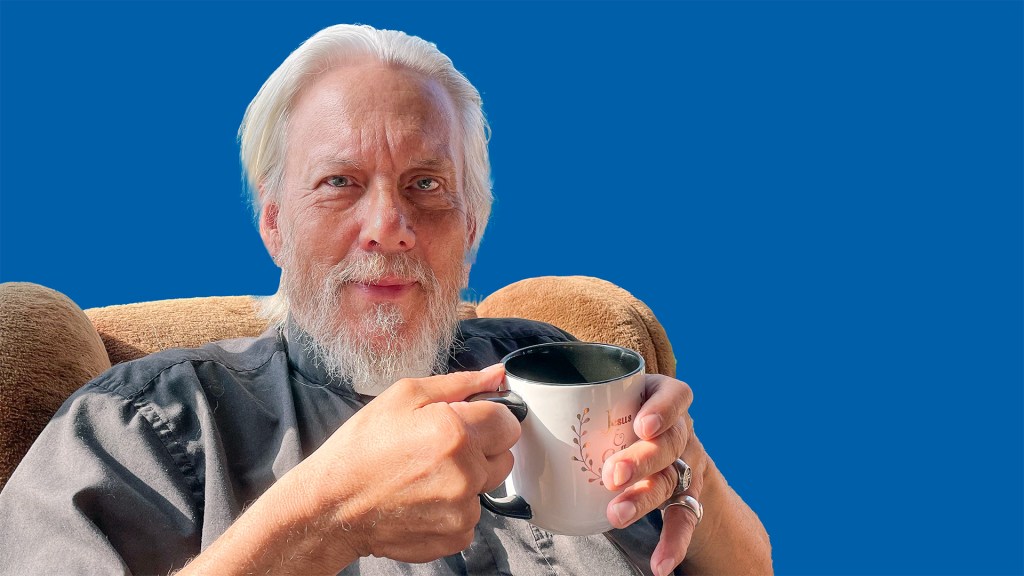

Winona resident and Lutheran pastor Paul Sannerud knows how unchristian Christian nationalist ideas are. In fact, he came to the DFL Caucus night this past February specifically to propose a plank rejecting Christian Nationalism.

“People who tout Christian nationalism do not remotely follow the practices that Jesus did. And that’s what’s frustrating,” Sannerud says. “Ultimately, they are using their religion as a screen to provide some sort of bolster for their political views. They’ve essentially said, ‘My politics are more important than my religion,’ and in the Judeo-Christian tradition they have just violated the first commandment—the first and biggest commandment.” The first of the ten commandments states, “You shall have no other gods before me.”

According to Sannerud, Jesus rejected the concept of state religion because the state, by definition, must rule by force, and Jesus had a different approach: “Jesus didn’t ask us to pick up arms for anyone, because he taught that truly love is the only thing that will change somebody’s heart. Yes, you can force them through fear and intimidation to do certain things, but you’ll never get them to change their heart. They’ll always be resentful, always breed more anxiety and foment violence in return.”

Sannerud says the willingness on the part of Christian nationalists to use state power to coerce belief demonstrates how far from the faith they have fallen—especially since the anxiety motivating them seems to be a fear of strangers, immigrants, and other kinds of people different from them. “The Gospel literally, in…dozens of places, entreats us to embrace the immigrant, to feed the hungry, to take in, to care for the outsider,” says Sannerud. “Jesus goes so far as to say, ‘What you have done to the least of these, you do to me.’ Or as Dorothy Day put it, ‘I only love God as much as I love the person that I love the least.’”

Sannerud says he is sympathetic to Christians who view the country as changing and becoming more diverse: “There are a lot of people who have a deep passion for their country, and they also have a deep passion for their religion—they ask, why aren’t the two the same? It’s a very seductive argument. . . the problem with it is that many people are not able to see that it masks a white supremacy position, an anti-immigrant position. It is a way of saying that, because I am white and have a job, I am somehow better than the immigrant or the person on welfare, which is completely antithetical to the Gospel.”

It is also antithetical to the Constitution, which is very firm on the importance of keeping church and state separate. Sannerud notes that many Lutherans came to America seeking religious freedom. Religious freedom means exactly that–no state coercion. “Within the community of pastors,” he says, “we have a real fear of letting the politicians define what Christianity is. That is what Christian nationalism wants to do, to say this is Christianity.’’ But what if you don’t agree? Sannerud says that the founder of Lutheranism, Martin Luther, “goes on at length about our responsibility as Christians to be active citizens, to participate in the mechanics of it, but not to use those mechanics to force other people to come to our point of view.”